The £3 Billion Question: What Really Counts as Public Health?

If we say yes to this, we are always saying no to something else

“To choose one thing is to turn away from another”

Every year, England spends over three billion pounds directly on “public health”. If you gave away one pound every second, it would take you 95 years to spend it all. But what exactly counts as “public health”?

Public health has expanded far beyond its original remit: sanitation, harmful housing, infectious disease control. Today, almost anything that affects wellbeing could be framed as a public health issue - from parenting classes to pothole repairs, from street lighting to loneliness.

This conceptual sprawl reveals a deeper issue: the idea of public health is boundless; but the reality is not. It’s easy to fudge what public health could be when there’s no shared boundary for what it should be.

This ambiguity has real consequences - practical, financial, and immediate. Most obviously, in opportunity costs.

You can’t fund everything. If more of your budget goes on social isolation and drug-addiction treatments then less goes on smoking prevention, obesity reduction, or mental health support. And it's not just money - professionals only have so much time, energy, and attention. Every new priority stretches the system, and people, still thinner.

This short piece explores how public health is defined, and how that can lead to big-budget consequences, hidden opportunity costs and a diluted professional focus.

It’s part of a series exploring:

The £3 Billion Question: What Really Counts as Public Health?

What kind of health thinker are you? 5 Foundational Questions

What kind of health thinker are you? 7 Ticklish Topics

Equality before freedom? What do we really value most?

Drawing the line with the Grant

One solution in practice is the public health ring-fenced grant – public money with strings attached. Like defining art by what artists make, some define public health by what this money funds.

It’s imperfect, contested, and occasionally absurd - but it's somewhere solid to begin.

Every year Councils in England receive a combined £3.8 Billion of public money to spend on “public health” in the form of ring-fenced public health grants.

The money ranges from £35 to £200 per head, depending on population size and need, totalling anywhere from around £10 million per year for a small Council serving around 200,000 residents, to over £100 million for the largest, Birmingham, with its 1.1 million locals.

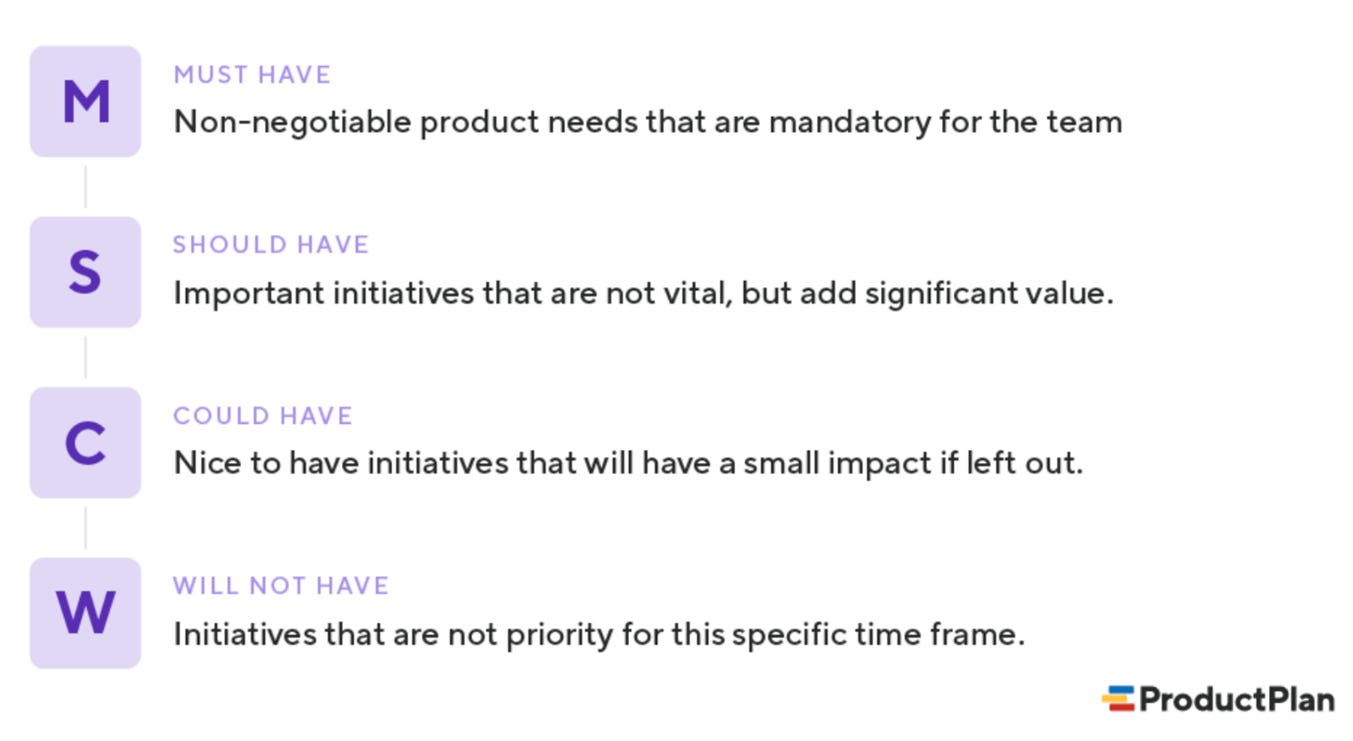

Below is the full list of all 36 categories under which it can be spent, further split into 7 “must haves” and 28 “should haves”. Think of it as the public health set menu.

The grant spend also competes with an infinite number of off-menu demands - ranging from mild to wild. These are the ‘could haves’ and ‘will not haves’ that often find their way in anyway.

Source: https://www.productplan.com/glossary/moscow-prioritization/

The 7 must haves - called prescribed or statutory functions - include a combination of trying to stop problems before they start, finding problems before they worsen, and managing disease.

Sexual health services - sexually transmitted infections testing and treatment

Sexual health services - contraception

NHS Health Check programme

Local authority role in health protection

Public health advice to NHS commissioners

National child measurement programme

Children’s 0 to 5 services

The 28 should haves - called non-prescribed functions – are also a mixed bag, but focus more on stopping problems before they start.

Sexual health services - advice, prevention and promotion

Obesity - adults

Obesity - children

Physical activity - adults

Physical activity - children

Treatment for drug misuse in adults

Treatment for alcohol misuse in adults

Preventing and reducing harm from drug misuse in adults

Preventing and reducing harm from alcohol misuse in adults

Specialist drug and alcohol misuse services for children and young people

Stop smoking services and interventions

Wider tobacco control

Children 5 to 19 public health programmes

Other children’s 0 to 5 services non-prescribed

Health at work

Public mental health

Test, track and trace and outbreak planning

Other public health spend relating to COVID-19

A “Miscellaneous” category then includes, but is not exclusive to:

nutrition initiatives

accidents prevention

community safety, violence prevention and social exclusion

dental public health

fluoridation

infectious disease surveillance and control

environmental hazards protection

seasonal death reduction initiatives

birth defect prevention

general prevention

Source: Public Health Grant Categories 2025

The Hidden Trade-Offs

For many, it’s surprising to find that some of the biggest contributors to preventable illness - smoking, obesity, inactivity, even bad backs at work - fall into the optional category. That means they can be squeezed to the point of ineffectiveness or cut entirely when budgets tighten. More still, they can be quietly crowded out as attention drifts by expansion or confusion.

Like any good list, it includes a chunky “miscellaneous” section, and within that, a wide-open “general prevention” line. What’s in there exactly? Good question. What counts as prevention - and what could or should be placed in that category - is significant and so is tackled in a different piece: The Problem with NHS “Prevention”

In practice, for councils facing huge social care overspends and mounting financial pressures, the public health grant can look like easy pickings. Especially when everything could be framed as public health. Around 25% of current spending already falls into this grey zone. These so-called “re-badged” funds - projects outside the traditional remit - are, at best, “could haves” never formally listed, and at worst, “will not haves” that snuck in anyway. They’re often justified under broad interpretations of well-being or stretching “general prevention” to its limit.

Each individual decision might seem harmless in the moment, even helpful - who wouldn’t want more public health activity? But with a scarce resource, every added could risks crowding out a higher-impact should. And over time, the cumulative effect is dilution.

If the Musts are fixed, and 25% of spending is already out the door on Coulds, then the obvious squeeze is on the Shoulds - right where many of the most effective interventions live. This is the hidden risk of scope creep, and the practical result of philosophically fuzzy boundaries.

People think focus means saying yes to the thing you want to focus on…

It really means saying no to the hundred other good ideas out there.

You should be as proud of the things you haven't done as the things you have.

- Steve Jobs

You can do anything, but not everything.

Conclusion

Public health can be framed as almost anything, because the idea of public health is boundless. But the practice is not. It’s shaped by scarcity: constraints on money, time, attention, staff, and skill.

Paradise is a walled garden - not a boundless desert. As Robert Frost put it, “Good fences make good neighbours.”

Public Health leaders know, but it’s always worth saying afresh, that every boundary we build, or fail to build, reflects a deeper choice - about what matters most, and what gets left out.

If we say yes to this, we are always saying no to something else.

Have we said yes to too much - or not enough? Either way, let’s choose wisely. And make those choices visible.

“Every choice is a boundary drawn. The question is whether we’ve noticed we’re drawing it.”

This article looked at what public health does do, bounded in practice by funding with strings attached. But we haven’t yet asked what public health should do - and to answer that, we need to ask what health really is.

That answer leads to radically different activities - all under the same ‘public health’ label.

Up Next: Health: Foundation or Flourishing? Is health the absence of disease - or a life well-lived?

If you enjoyed the article, you can now Buy Me A Coffee to show your support.

Reflections from the “1,000 Fragments of Insight” project

These ideas pair well with public health thinking - or any big decisions worth making.

Freedom is choosing your own restraint. Not, freedom from choice.

Sometimes people try to avoid mistakes by not making a decision, but not making a decision is still a choice that has consequences.

If you don't decide you drift, because you don't put your agency behind anything… Without any firm values, anchors, or knowledge of what you are for or against, the default is to be drawn towards superficial rewards or away from punishments. This is a shallow existence.

There is no best option, simply a choice about what to put your agency behind. A courageous chance to say… I'm the sort of person who will…who does…

Hard choices aren't comparable because values (beauty, freedom, self-expression) aren't quantifiable. There is no better, same or worse option. They are different in different ways.

Uncouple decision making from consequence at your peril.

The more things we try to do at once, the less we do any of them well

The most powerful ideas in a system are the ones never named aloud

Naming the shape of a thing is the first step to acting on it

If you enjoyed this, you might also enjoy

The public’s health:

The £3 Billion Question: What Really Counts as Public Health?

What kind of health thinker are you? 5 Foundational Questions

What kind of health thinker are you? 7 Ticklish Topics

Equality before freedom? What do we really value most?

Wisdom 1,000 Project

1,000 Fragments of Insight - Introduction (1 min read)

1,000 Fragments of Insight - Culture (39 min read)

1,000 Fragments of Insight - Mindset and Growth (31 min read)

1,000 Fragments of Insight - Existence and Meaning (29 min read)

1,000 Fragments of Insight - Morality, Ethics and Beauty (38 min read)