Responsibility without Blame

In seeking to avoid blame, have we lost the idea of responsibility?

The Thought Terminating Cliché

Many friends, family members, nurses, and doctors have avoided conversations about harmful weight for decades. A common worry is that “its blaming people.”

Psychiatrist Robert Jay Lifton described phrases like this as thought-terminating clichés.

In his 1961 book Thought Reform and the Psychology of Totalism, based on his study of Chinese Communist “re-education” camps: he identified these clichés as part of ideological control, where complex thoughts are reduced to pre-approved, slogan-like phrases to shut down critical reflection.

The cliché differs but the goal is always the same: halt questioning, signal social or moral superiority, and replace analysis with obedience. They are surprisingly common in personal and professional life if your antennae are tuned.

If society wants to deal in truth and impact (a huge if), we must decline these frequent invitations.

One starting place is re-learning the skill and confidence of talking about responsibility without blame.

Why This Matters

Many midwives, nurses, doctors, paramedics, health visitors and other health workers have avoided conversations about smoking or harmful body weight for decades out of well-meaning fear they will provoke blame or shame; or be thought a fraud by dolling out advice while sat in the same boat. But inaction can be as harmful as action. Kind can be cruel.

Most smokers want to quit. Most people would like to lose weight. By side-stepping a conversation through lack of will or skill, we prevent people accessing the support they want. If you multiply this up at a national level, we’re missing millions of constructive conversations every day, and that is adding up week by week, year by year.

In other professions like coaching, therapy, social work, and education, responsibility is addressed routinely and constructively with no shame or blame in sight. Practitioners help individuals take ownership within their context, no matter what it is, fostering insight, resilience, growth and control.

Public health tries to do the same, but history shows us we, like broader society, swing from one imbalance to another: all personal responsibility for one season, all structure and context another.

The Pendulum Problem

In the past, health was seen as a personal matter. People understood that poverty and housing played a role, but they also believed that individuals had choices within those constraints and that those choices reflected their character, for better or worse. Habits like cleanliness, body weight, alcohol use, gambling, piety, and smoking were considered personal responsibilities. They were viewed as expressions of self-control, fortitude, and resilience - virtues society valued and wanted to encourage.

You had the socially sanctioned choice to be dignified and trustworthy, even in misfortune, and at any level of society. That was the carrot. Shame, for digression, was the stick.

Today, at least in health professional circles, we no longer tether people’s health to their willpower or, by extension, to their moral character. We instead recognise how environments, income, advertising, housing, and culture shape thought and action. As a result, we have many “structural” and “contextual” models that now dominate public health thinking, and public policy more broadly. These models shape how problems are understood, and so downstream, what range of solutions are visible or hidden. They shrink the full buffet of possibilities down to a curated set of options that fit the frame.

Contextual models emphasise how conditions in which people are born, live, work, and age - like housing, education, and income - shape health outcomes. They are almost always factors beyond individual control. Examples include the Social Determinants of Health, Place-Based Health Equity Models, Doughnut Economics, Planetary Health, Commercial Determinants of Health, and Health in All Policies.

One of the unintended consequences of embracing the language of social determinants of health over the last 30 years, is that more and more people think that environment is destiny. The wider determinants of health start to sound like the only determinants of health.

I’ve seen this happen in conversations with both the public and fellow professionals.

This shift of emphasis from person to place corrected a real psychological blind spot. But today, there are many who’ve heard only this dominant view. They are not aware of the many alternatives or it’s blind spots (See Appendix A: 11 Models to Keep in Mind).

The counter argument is that there are many models to choose from. And that is true. But some models dominate more than others, they stick around and hold more sway than most in professional and public circles, and it’s the structural ones that are most in fashion for now.

When they linger for long-enough people are lured into thinking that one lens can rule them all and get idle waiting for one type of change to fix everything. And if that change must come from outside, we learn helplessness.

One Lens to Rule them All

Outstanding teacher and theoretical physicist Richard Feynman once remarked that any scientist worth their salt must hold multiple theories in their mind at once. Because each one reveals different questions and blind spots. Relying on a single lens forces you to ignore the data that doesn’t fit, or practice mental gymnastics to preserve your preferred lens. Public health needs the same agility and humility.

Marx saw history as a struggle between classes. Foucault saw it as a web of power. Freud saw the mind as ruled by the unconscious. Economists saw people as driven by incentives. Feminism saw society as shaped by gendered conflict. Christianity saw life as a journey of redemption through love. All have a partial truth, none has the full story.

So, all that is to say, I have been considering whether the pendulum has swung too far and for too long toward structural explanations of health. In seeking to avoid blame, have we lost the idea of responsibility, and are we under-using other lenses (See Appendix A: 11 Models to Keep In Mind)?

To explore this, I've attempted a new format, a disputation. I’d welcome any extra objections and responses in the comments to flesh it out.

My Claim

Public health should reclaim the skill of talking about responsibility without blame.

A Disputation

Objection 1:

“Discussing personal responsibility equates to blaming individuals, especially those in poverty.”

Response:

Acknowledging responsibility does not deny context. Instead, it invites individuals to act within their circumstances. Denying agency can be dehumanising, suggesting people are mere products of their environment. There are some moral theories that rely on people making choices. If people are denied choice, no matter how restricted, they are denied the chance to be moral.

Objection 2:

“Structural factors predominantly determine health outcomes; focusing on individual agency distracts from systemic solutions.”

Response:

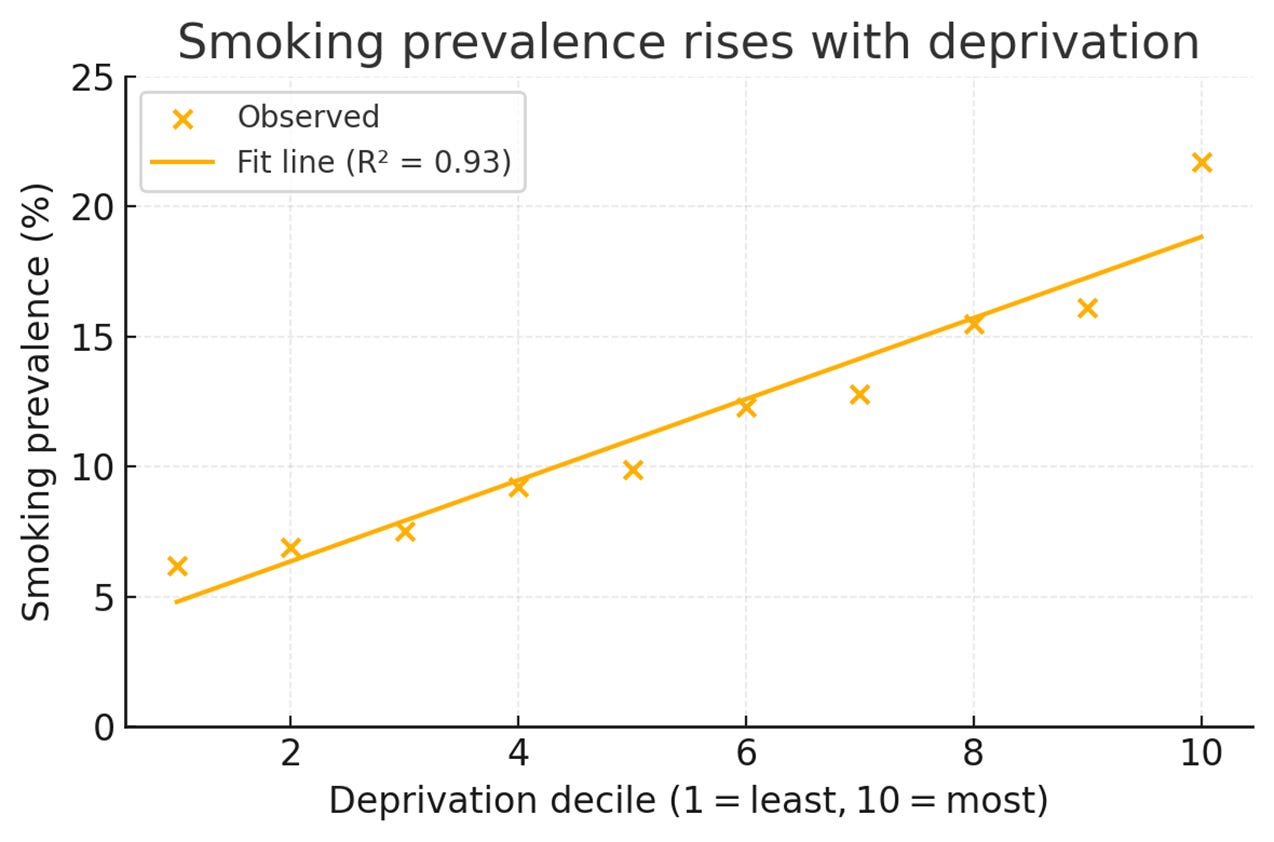

Structural factors are real, but they are not deterministic. Strong group trends can be weak at an individual level. The link between smoking and poverty is a good example of this: despite higher rates of smoking in deprived areas (a 93% predictive fit), most people in deprived areas still do not smoke. Public health must address systems and support agency to be effective (See Appendix B: Smoking and Deprivation for the case study).

Objection 3:

“Emphasising responsibility leads to stigma and punitive policies.”

Response:

That risk is real and was the case in the past, but the answer is precision, not avoidance. The distinction between blame (assigning fault) and responsibility (enabling action) matters and is possible to make. Other fields manage this distinction well; public health can too.

Objection 4:

“People may feel judged when responsibility is discussed; it’s safer to avoid the topic.”

Response:

Avoidance is not safe, it harms. Most people want to stop smoking, most want to lose weight, so not having those conversations through lack of skill or confidence is a missed opportunity. It also potentially places professional timidity over patient care or duty. Health professionals need skills and tools to talk about responsibility without blame or judgement, which is possible.

Objection 5:

“People’s responsibility is so small in the grand scheme of things, focus on the bigger picture.”

Response:

That might be true in some cases, but less true in others. I don’t think we can make that claim as a default. If we’re able, we can parse out factors that are in an individual’s control and influence, and work on those, leaving those outside of their control as up to someone else. That avoids all or nothing thinking and invites precision and targeted action allocated to different actors: the citizen, the professional, the health system, civic culture etc (See Appendix B Control, Influence and Beyond examples for smoking and deprivation).

Conclusion

At one extreme, we can imagine perfectly autonomous individuals who could transcend any environment. At the other, we can imagine people so shaped by their environment that they become inert, lacking any free-will, like a stick floating down a stream.

Neither is fully false, nor true. The sweet spot lies somewhere in the middle and may look quite different for something like obesity compared with smoking. Aristotle’s Golden Mean describes not an exact midpoint but a contextual balance between excess and deficiency. To get at where that might be, we need to sift through the causes as best we can and divvy up the points of action at the appropriate level: what’s in the control or influence of the individual, and what’s in the control and influence of the environment. A responsible civic collaboration of give and take.

Those of us interested in society and wellbeing don’t have to be a Nobel prize winning theoretical physicist like Feynman, although that would no doubt help. We can aim at something more modest. To always be aware that one lens is inadequate, no matter how fashionable or socially sanctioned. In seeking perspective, all we need to do is consider that we are sitting atop a seesaw, what then, is the idea sat at the other end? And what other rides are available in this playground?

Public Health must perform the dual balancing act of engineering an environment that can empower any individual, while simultaneously empowering an individual to exercise their self-rule in any environment. In my view, skip the individual and your equation is incomplete.

A digestif for your efforts: A Master Teacher and Entertainer in Action.

Feynman: Knowing versus Understanding (5:36)

Feynman on Scientific Method (9:58) – a true masterpiece

Coming soon

Civic Health – Virtue Ethics and Public Health – a Thought Experiment.

Appendix A: 11 Models to Keep in Mind

1. Structural Contextual Models

Health is shaped by structural factors like housing, income, education, and power dynamics that lie beyond individual control.

2. Strengths-Based or Agency-Oriented Models

Empower people and communities by building on their existing strengths, autonomy, and capacity to improve health outcomes.

3. Psychosocial and Behavioural Models

Individual choices, stress, and social context shape health behaviours and can be influenced through support, motivation, and education.

4. Rights-Based and Political Models

Health is a human right, and public health must confront injustice, amplify marginalised voices, and protect civil liberties.

5. Systems Thinking & Complexity Models

Health emerges from dynamic, interdependent systems, requiring feedback-aware, adaptive, and multi-level approaches to intervention.

6. Holistic and Integrative Models

Health is a balance of physical, mental, emotional, social, and sometimes spiritual wellbeing, requiring coordinated and inclusive approaches.

7. Biomedical Model

Health is the absence of disease, understood and addressed primarily through biological and clinical science. Maps Schopenhauer – to be happy, avoid suffering.

8. Salutogenic Model (Protective factors)

Focus on what creates health, like meaning, purpose, and coping skills, rather than merely preventing disease.

9. Ecological Models

Multiple layers of influence - from individual to policy- interact to shape health, requiring action at all levels.

10. Capability and Flourishing Models

Health means having the freedom and opportunity to live well, focusing on dignity, autonomy, and potential rather than just risk reduction.

Feel free to suggest your own for religious or economic lenses, for example, I’m a fan of the phrase

“Show me the incentive and I’ll show you the behaviour.” This could lead to a cheeky 11th model …

11. Economic and Incentive-Based Models

Health outcomes are shaped by costs, incentives, and choices, and aligning these wisely is key to changing behaviours and systems efficiently.

Appendix B Smoking and Deprivation

In England, smoking rates vary dramatically by deprivation (See Above). For example, in 2023, 21.7% of adults in the poorest areas of England were smokers, compared with 6.2% in the richest. A full 15.5% difference.

Run the stats, and you can find out that 93% of the variation in smoking rates between areas is explained by their level of deprivation (rich or poor). If you knew nothing but an area’s deprivation score from one to ten, you could predict its smoking rate with 93% accuracy. Which is unusually high.

So you might conclude that 93% of smoking is caused by the environmental conditions in which people are born, live, grow, work and age, leaving just 7% to individual manoeuvring. And if you believe the environment is destiny, the hat fits.

But that’s a trap. The distinction between group patterns and individual behaviour is crucial. Stats, like science, is where instincts and common-sense lead to ruin more than reward.

Have a look at those figures again. You can predict smoking levels to 93% accuracy knowing only the area deprivation, yet, even in the most deprived areas the vast majority of people still do not smoke. In the poorest 10th of society 21.7% smoke, so that means more than three out of four do not (78.3%). That usually grinds the gears of the mind…so if it does, don’t worry, you’re not alone.

The short answer is ecological fallacy. You can’t reliably draw individual conclusions from group data. Said differently, the group pattern is real and fits neatly - but it’s not deterministic or strong at an individual level. Not by a long shot. If it were, you’d expect closer to 100% smokers in the most deprived areas, not 21.7%.

The difference is that there are always far more individual variables that make it more or less likely a person will smoke than at the group level. The individual is always more diverse than the group, as the individual is the end point of all group intersectionality. Something Western culture worked out about 2,000 years ago, starting in the Middle East, but that we like to find new ways of forgetting.

Control, Influence, or Beyond?

Leaving group deprivation aside and looking just at the individual factors for a second. Lots of variables go into the odds of someone smoking as an adult. Not everything that affects smoking is a personal choice - but not everything is out of your hands either. Here's an example of a way to think about it (and other public issues) that leads to clarity on who can help and how:

In Your Control

Beliefs about smoking (e.g. stress relief)

Motivation and readiness to quit

Daily habits and triggers

Use of stop-smoking aids (patches, apps, vapes)

Seeking out supportive environments

Learning about health risks and benefits

Developing coping strategies (e.g. urge-surfing, mindfulness)

Within Your Influence (with support)

Managing mental health

Reducing stress from life circumstances

Changing peer and social norms over time

Overcoming nicotine dependence

Building impulse control

Beyond Your Control

Whether you grew up around smoking

How early you started

Your education level

Where you live and how deprived it is

National tobacco laws, pricing, and advertising

Cultural norms you were raised with

This way of framing things validates people’s realities while still showing where change is possible.

You can’t precisely divide smoking into neat buckets of "personal" or "structural", but a rough estimate might look something like this as a proof of concept. If anyone has run the actual numbers (theoretically possible [I think]) do let me know:

Influence Type and rough share of total variation

Structural (not controllable) 40%

Constrained but modifiable 30%

Personally controllable 30%

A substantial portion could be out of an individual's hands – a structural concern for them, and target for politics, the economy or civic culture. Some might be changeable with help – constrained but somewhat modifiable. And a final chunk – possibly a minority but still a significant part of the story - is in our direct control. You can see why luck, fate and destiny were so high on the Ancient Greek’s cultural list after all.

The central question the smoking example raises is a big one: How do we reconcile clear group-level patterns with the reality of even greater individual variation? Some cultures, and even the same culture at different points in history, emphasise the group, others the individual. I’ll leave that one with you...

I agree that at times the structural determinants are over emphasised or perhaps inaccurately described (over simplified discussions concerning variables and their influence on health outcomes). An example being models that emphasis the % of health impacted by environmental factors Vs medical Vs behavioural for instance.

My slight challenges and thoughts are:

I think "good" public health practice draws also on wider theories that recognise individual behaviour - COM-B as a fairly balanced model. Also power dynamics theories such as those that explore empowerment, and assets based approaches to practice. Those recognize the harm in viewing populations impacted by inequitable structural hazard exposures as being passive / in need etc.

I think in practice there is recognition that front line professionals who are well placed to have conversations about behaviors lack either the competence or confidence or both to challenge unhealthy behaviors and there are training programs aimed at addressing this. How well communities and individuals feel it socially acceptable to challenge behavior of friends and family I am less confident in and unsure how much that has changed.

Finally, I think in part the emphasis in practice on structural factors is about influencing resource allocation. So for example, some services such as access to smoking cessation may require less advocacy while the need for better quality housing may be seen as a factor that requires more emphasis?